The Beauty of Brutalism

The recent Oscar-winning film, ‘The Brutalist’, has sparked new interest in brutalist design and has begun to influence design. At a time when luxury and extravagance dominate interior design trends, the rawness and honesty of brutalist architecture is like a breath of fresh air.

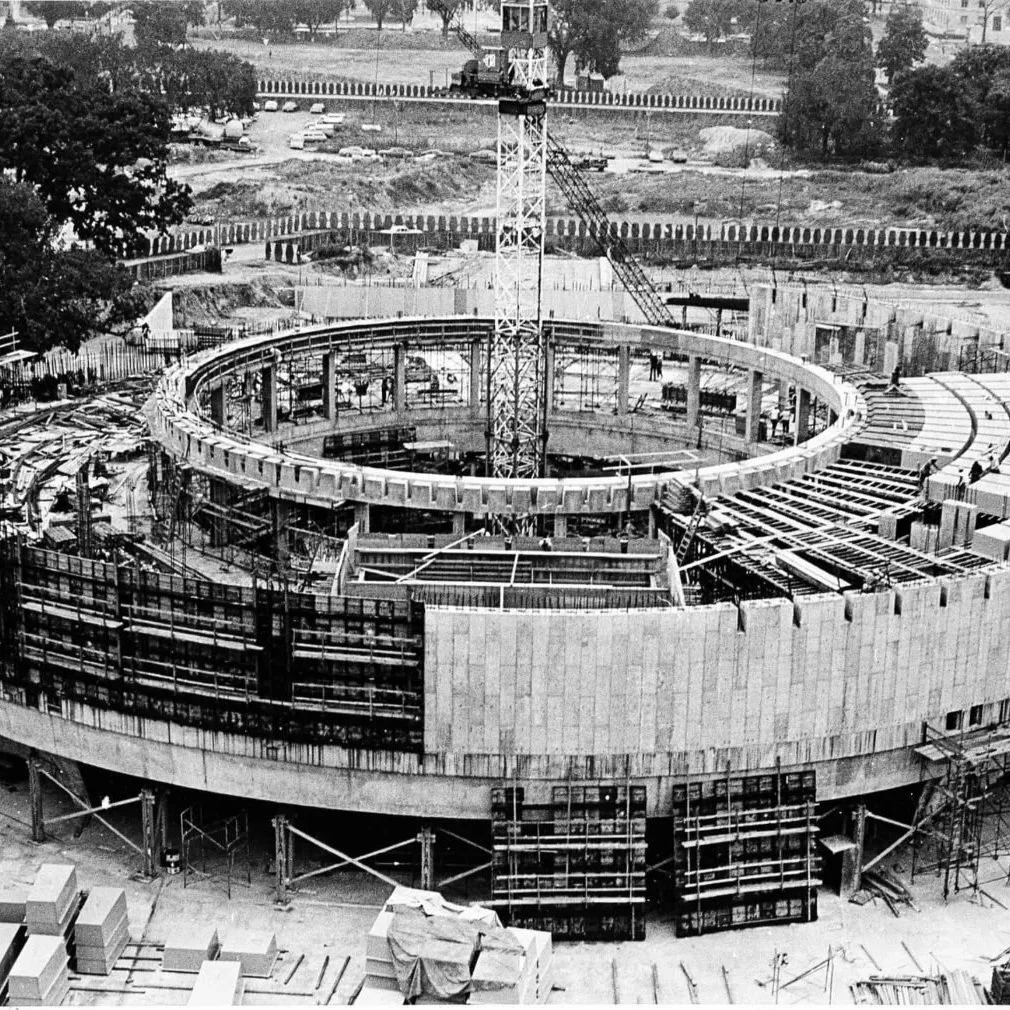

Speaking of brutalism, many may assume the term refers to the “brutal” appearance of the buildings themselves. However, it originates from the French phrase ‘béton brut’, meaning “raw concrete”. Brutalism peaked in the UK during the post-World War II era, ideal for large-scale public buildings due to its efficiency, cost-effectiveness and minimal decorative needs. By the 1970s, it fell out of favour as public preference shifted towards warmer, less imposing designs.

Expressively Raw.

Brutalist architecture stands out from afar with its raw aesthetic. Exposed concrete is predominantly used, emanating a striking, cold presence, often complemented by other unrefined materials like brick, steel, and glass. Lavish finishes and decorative elements are seldom found, exuding a utilitarian feel. The massive scale and bold, geometric forms, typically angular or monolithic, creates an imposing, sometimes overpowering effect on passersby.

Despite its stark, often bleak appearance, Brutalism is a deeply expressive architecture style. Its enormous size of stacked forms is a realisation of bold geometries, brought to life by the unapologetic use of raw, exposed materials. It celebrates raw materials such as concrete, in its unadorned, monochromatic state, stripped of embellishment. By showcasing materials in their purest form, unveiling their innate textures and properties as whole, Brutalism reveals the essential function of a structure without extravagance. The powerfully bold honesty in design and architecture marks the raw potential in Brutalism.

The striking nature of Brutalist architecture can be daunting, with its rigid concrete forms and austere presence.Yet, when paired with soft, flowing organic elements, this sharpness and heaviness transform into a strong chemistry, blending bold intensity with delicacy.

Living With Brutalism.

Brutalist architecture, while not completely rare in Hong Kong, flourished from the 1960s to 70s. An example is St Stephen’s College Special Room Block, designed by Tao Ho in 1981. Its bold outlook, consisting of raw concrete and bulky geometry forms, embodies the brutalist influence.

What is distinctive about the space is its tilted concrete walls, accented with transparent facades. This design diffuses sunlight, preventing direct exposure while reflecting light to moderate the interior temperature of the sports area. Serving as a natural cooling solution due to the absence of air conditioning for cost reasons, this smart and functional design reflects the creativity of its era.

We have also integrated a refined Brutalist aesthetic into 再敘三點三, our first full-service project in Longhua District, Shenzhen, to honour the district’s industrial heritage.

The interior design of 再敘三點三 is dominated by raw concrete, with concrete walls and seat dividers adding on to the immersive Brutalist experience. Metal elements, including stainless steel and metal frames, can be observed at the striking facade accentuated with circular windows, tables, bespoke lighting, and intricate details.

A standout feature with a Brutalist touch is the terracotta tiles at the takeaway counter, adding a rustic charm while echoing to the brand’s colour palette. This bold yet minimal material selection reflects the area’s industrial roots, maintaining a cohesively Brutalist aesthetic.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading this little tour through the world of Brutalism. Subscribe below for exclusive insights into our bespoke designs, or schedule a free consultation to see how we can create your ideal space.